02. Further Research¶

Complex Geometries¶

Gyroid¶

The gyroid is a 'triply periodic minimal surface' - defined by its zero mean curvature and locally area-minimizing properties. It is composed of intersecting 2D wavy lines, with an absence of straight lines 1 .

Photo by Wolfram Aplha on "Gyroid"

The gyroid infill pattern used in 3D printing is known for its great strength to weight ratio. It provides excellent load bearing capabilities making it an ideal choice for parts that require durability and resilience. Gyroid shapes are also highly efficient in terms of material usage - the interlocking channels and lattice pattern decrease the volume of material, which minimizes material waste and lowers costs.

These properties are great and allow for maximum material efficiency without compromising strength or structural integrity. I believe combining this structure with 3D bioprinting for the purpose of coral reef restoration would provide an excellent solution to the problem stated.

The structure contains varying heights, channels, platforms and a high surface area for optimum marine life attachment.

3D BioPrinted Calcium Carbonate Gyroid Structure¶

Photo by Olupsi on "Hanging Fish House"

As part of the Buoyant Ecologies Float Lab, Alex Schofield designed these hanging prototypes - 3D printed using calcium carbonate. Titled 'Hanging Fish House', they are computationally designed providing spatial alcoves for a range of marine life.

Photo by Olupsi on "Hanging Fish House"

Photo by Olupsi on "Coral Carbonate"

3D Printed Gyroid Ceramic Jewellry¶

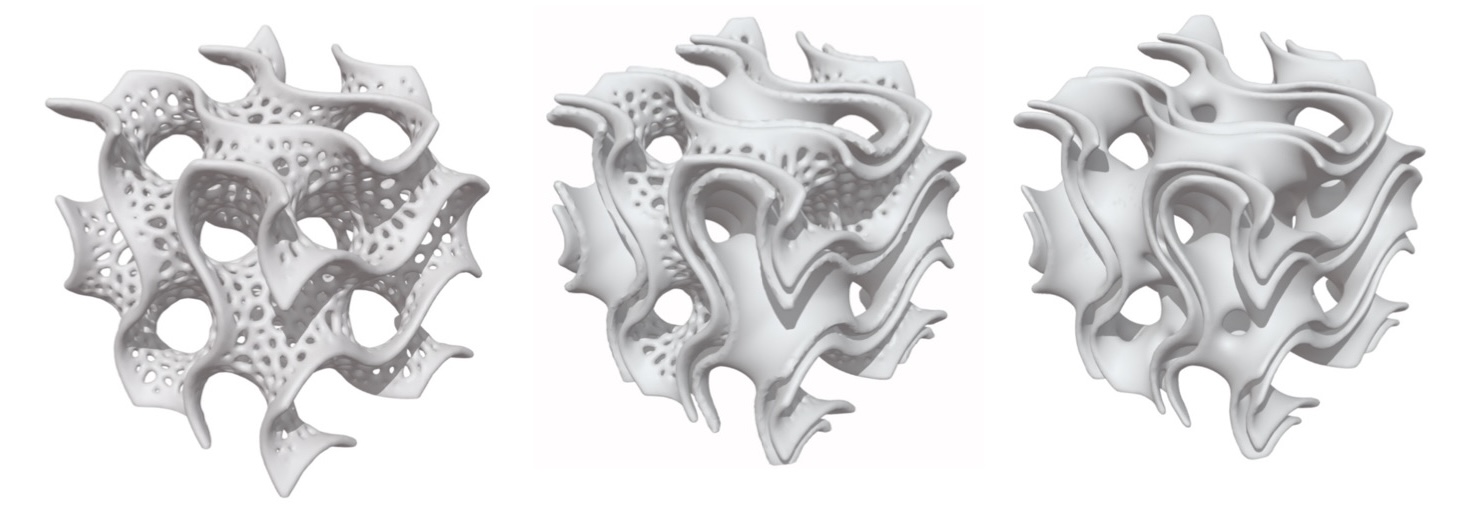

Porifera is a jewellry collection created by Nervous System inspired by deep sea sponges which build reefs with complex and porous architectures. Nervous System used computational design methods to generate minimal surface networks along cellular scaffolds using FormLab's ceramic resin 3D printer. Using gyroid structures in their designs allowed for continuous, self-supporting structures to be formed.

Gif by Nervous System on "Porifera - 3D Printed Ceramic Jewelry"

Photo by Nervous System on "Porifera - 3D Printed Ceramic Jewelry"

• • •

Voronoi¶

A Voronoi pattern is a type of tessellation in which a number of points scattered on a plane subdivides in exactly n cells enclosing a portion of the plane that is closest to each point.

Whilst researching I found a model on Thingiverse which combines both voronoi and gyroid structures which could make a very interesting artificial coral reef structure.

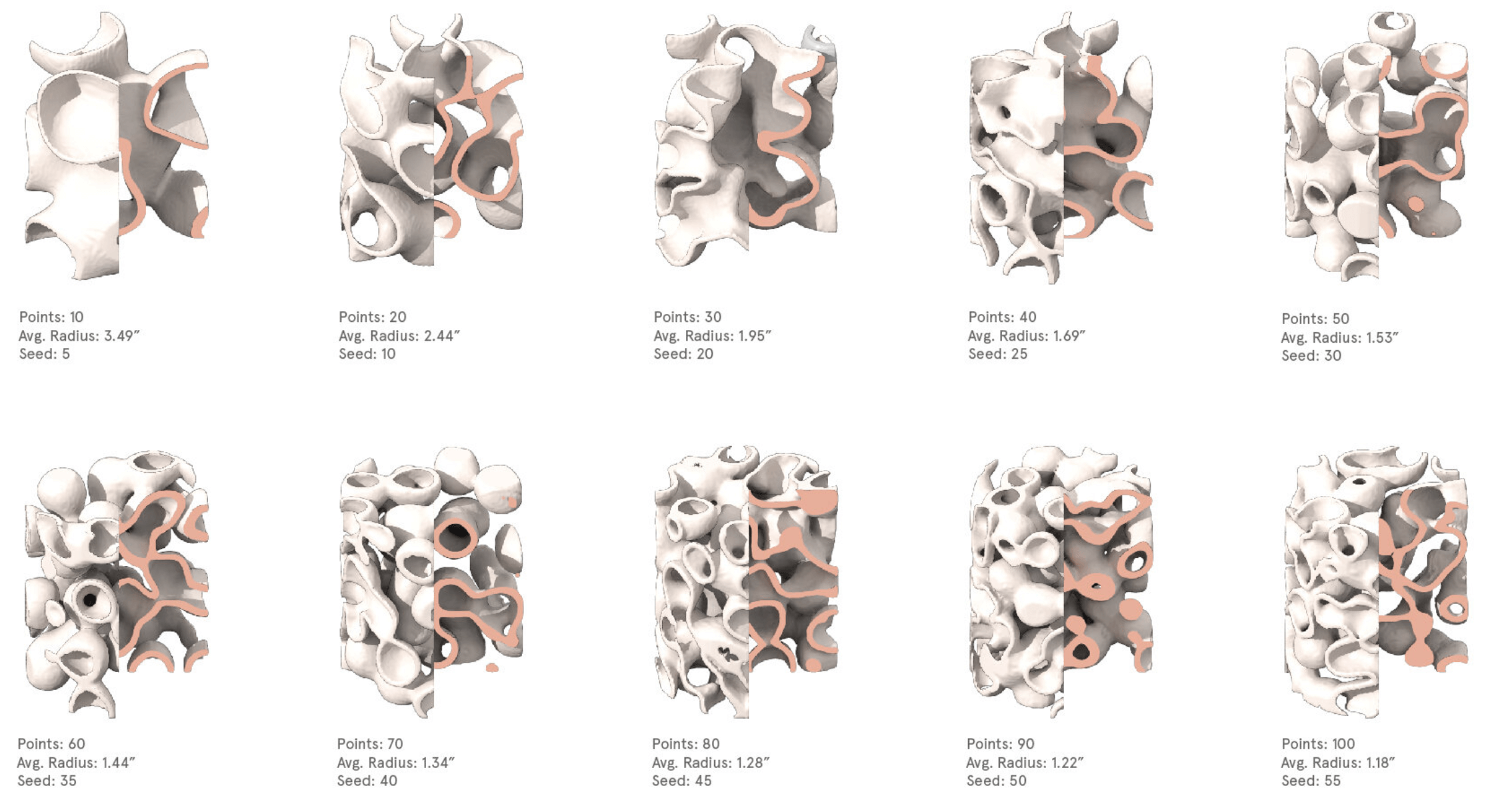

A Single Gyroid Surface in a Voronoi Pattern | Two Offset Gyroid Surfaces - one solid, one voronoi | Two Solid Offset Gyroid Surfaces Connected With 'Wormholes'

It would be interesting to explore whether these structures could be made into a modular piece that slots into another to create a unit.

• • •

Fischer Koch - S¶

Fischer-Koch-S (FKS) are another type of triply periodic minimal surface (TPMS).

Photo by Thangs on "Dave Makes Stuff - Fischer"

In the research paper 2 FKS scaffolds were fabricated in ceramic and compared against a Gyroid surface structure for the potential application in bone tissue engineering.

The results showed that FKS scaffolds were:

-

32% stronger

-

absorbed 49% more energy

-

had 11% lower permeability

when compared to the Gyroid scaffolds manufactured at 70% porosity. TPMS have a high surface-to-volume ratio and interconnected porous structures which optimise cell attachment, making them ideal structures to consider for artificial coral reef.

Microbial Induced Calcite Precipitation (MICP)¶

MICP is a nature-based technqiue which involves using bacterial processes to produce a calcium carbonate bio-cementation within a soil matrix to enhance soil properties such as unconfined compressive strength (UCS) 3,4 .

The following articles have been analysed to better understand the MICP processes!

3d Bioprinting of Mineralizing Bacteria

The research documented in article 5 investigated 3D bioprinting living building materials which incorporated the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7002 which is capable of producing calcium carbonate (CaCO3). The bio-ink used was based on alginate-methylcellulose hydrogels containing up to 50 wt% sea sand.

Cell viability and growth were examined after the printing process (over 14 days) through:

-

fluorescence microscopy

-

chlorophyll extraction

The cells were able to withstand pressure and shear stress during the extrusion process and calcium carbonate mineralization was observed in the bioprinted material.

This research made me wonder.. since cyanobacteria are aquatic microorganisms does this mean that the material above could carry on functioning in the sea?

3D Printing of Living Structural Composites

Furthermore, the article 6 provided a great overview and research process of 3D printing of living structural composites. Undergoing MICP by urea hydrolysis from bacteria-loaded microgels allowed biomineral composites possessing up to 93 wt% CaCO3 and bearing loads up to 3.5 MPa (similar to the human trabecular bone) to form. Ureolytic bacteria used for these application must have a reliable, high urease activity, while being harmless to humans and pose low risk to the local ecosystem. Sporosarcina pasteurii was selected due to its high-urease activity and biosafety.

The process involved:

-

fabricating gelatin microgels containing the ureolytic bacteria, Sporosarcina pasteurii.

-

'jamming' the microgels form a 3D printable granular bioink (BactoInk) that can be converted into load-bearing biocomposites through MICP.

According to this paper microgels must be:

-

biocompatible

-

solidify under conditions compatible with bacteria

-

jam if up-concentrated to enable 3D printing.

Gelatin-based microparticles were found to satisfy all these requirements.

- dispersing freeze-dried S. pasteurii in a gelatin solution at 37 °C

- emulsifying the aqueous solution with mineral oil under vigorous stirring

- cooling the emulsion to room temperature

- washing the resulting microgels several times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to remove the oil and any unreacted moieties

- resuspending the microgels in a solution containing alginate (serves as a stabilizer)

- jamming the suspended bacteria-loaded microgels by centrifugation yielding the 'BactoInk'

put photo from research doc here

MICP Results: [after 4 days of incubation]

-

mineralization increases up to 20% if the urea concentration is increased from 0.05 M to 0.25 M, independent of the CaCl2 concentration By contrast,

-

for urea concentrations >0.25 M, the urea or CaCl2 concentrations did not affectthe degree of mineralization

The researchers chose a solution containing 0.75 M urea and 0.5 M CaCl2 to ensure maximum precipitated CaCO3 yield. The bacteria produced up to 77 wt% of CaCO3 within 24 h, and up to 93 wt% after 4 days of incubation

TIP!

Over-mineralization can be prevented by reducing the urea concentration, lowering the solution pH, or immersing the sample in ethanol to reduce the bacteria activity.

Process:

- prepare a PBS solution containing 25 wt% gelatin and maintain at 37 °C to prevent gelation

- add 1 wt% of freeze-dried S. pasteurii to the gelatin solution

- emulsify the gelatin-S. pasteurii solution by adding mineral oil with 2 wt% Span80 in a 3:1 volume ratio

- gel the emulsion at 4 °C for 30 min and then centrifuge it at 3000 rpm for 15 minutes at 20 °C (Mega Star 1.6R, VWR) to remove the majority of the oil

- remove the remaining oil and surfactant by resuspending the microgels in PBS and centrifuge them, the supernatant is discarded

- repeat five times and store the microgels at −20 °C

- prepare a PBS solution containing 5 wt% alginate is and mix with the bacteria-loaded microgels at a 4:1 weight ratio

- centrifuge the suspension is centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 minutes at 20 °C and discard the supernatant

- store the BactoInk at −20 °C prior to further use.

- load the BactoInk in a 3 mL Luer-Lock syringe and remove trapped air by centrifugation at 3800 rpm for 1 min at 20 °C. [3D printing of BactoInk was performed with a commercial 3D bioprinter (BIO X, Cellink)]

- extrude the BactoInk through a 21 G needle, using a pressure driven piston operated at 70 kPa with a printing speed of 10 mm s−1.

- printed samples are gelled in a 1 M CaCl2 solution for 30 min

- prepare prior to biomineralization, two aqueous stock solutions containing 1 M CaCl2 and 1.5 M urea with 0.8 wt% yeast extract respecitvely

- mix the two solutions in a 1:1 volume ratio before use

- add the gelled BactoInk sample to initiate the biomineralization

- exchange the solution every 24h for four days

- after the fourth day, remove the samples from the biomineralization solution, soak them in ethanol for 30 min, and dry in a vacuum at room temperature for 48h

Also on this article, methods for: determining the rheology of BactoInk, preparation of pre-mixed CaCO3-hydrogel composite, etc

UCS Testing:

Cylindrical samples were made and tested under uniaxial compression.

-

no significant change in stiffness was observed for samples after 24h of mineralization compared to the unmineralized polymer

-

after 4 days 'the mineral network was sufficiently robust for a cross-section of 50 mm2 to bear loads up to 175 N under compression'. UCS = 95 MPa, a value that is 3x higher than that of the unmineralized composite.

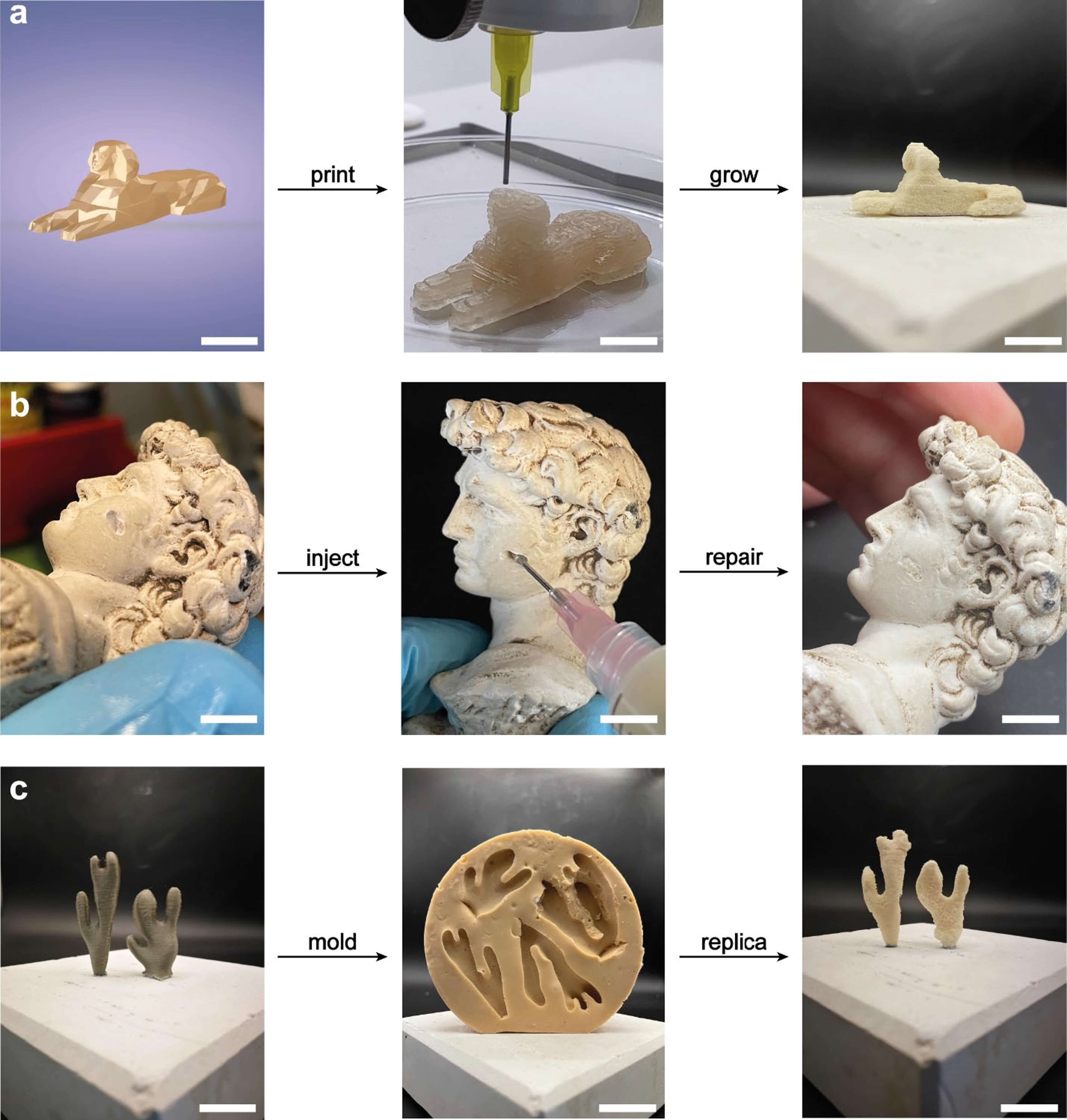

Photo by Science Direct on "3D Printing of Living Structural Composites" "Proof of concept of BactoInk biomineral composites: a, 3D printing of BactoInk into a sphinx | b. Application of BactoInk as a repairing paste for art restoration | c. Replica molding of corals"

This has proved to be a very helpful article containing potentially useful instructions on how to manipulate bacteria to be 3D printed. The question still rises though whether clay will mineralize under similar conditions. However, having to fire the clay after calcification would destroy the formed calcium carbonate.

Calcifying Bacteria¶

Comparison of Mineralizing Bacteria

The research article 7 focused on isolating and selecting bacteria capable of producing CaCO3 for bioconcrete applicatoin. Initially, eleven bacterial isolates were obtained of the genus Bacillus, Lysinibacillus, Exiguobacterium, and Micrococcus. Through various test such as thermogravimetric analysis; X-ray diffraction; and scanning electron microscopy, the strains were compared based on calcium carbonate production. Bacillus sp. and Lysinibacillus sp., produced the up to 80% CaCO3, the highest of all the strains.

Factors Affecting Mineralization

The Bacillus group was further mentioned in article 8 due to its high levels of urease , especially Sporosarcina pasteurii ( or formerly Bacillus pasteurii), meaning that under urea hydrolosis this bacteria is an ideal candidate for MICP.

The factors affecting MICP efficiency were evaluated as:

- type of bacteria

Bacillus group are the most commonly used in MICP. S. pasteurii has been used for remediation, concrete remediation and soil improvement. Another example is B. megaterium, which has been used to improve concrete hardness.

- concentration of bacterial cells

High bacterial cell concentrations increase the amount of calcium carbonate precipitated by MICP, thus increasing the concentration of urease for urea hydrolysis.

- pH

MICP is carried out at a pH between 7.0 and 9.5, depending on the strain of bacteria used. When pH levels are too low, CaCO3 dissolves.

- temperature

Like pH, required temperature for hyrdolysis is dependent on the strain ranging from 20 to 37 ° C.

- sources of nutrients

• • •

Sand, Bacteria and Urea¶

Exploring the process used to make biobricks has been useful in understanding whether I could 3D print with sand and sodium alginate, inoculating the structure with a calcifying bacteria and spraying it with urea.

Sand / Shells and Sodium Alginate in 3D Printing

The research in 9 explored using shells and sand as fillers in 3D printing. Chicken eggshells apparently contain 95% calcium carbonate proving to be a valuable filler. The methodology involved mixing sand or shells with sodium alginate and glycerine as the plasticiser and curing the structure by spraying 10% calcium chloride onto it. The structures were dried at room temperature.

Results were limited but concluded that the sand filler appeared to be a strong composite and the egg-shell based structure created a ceramic result.

Dune Sand Strengthening Using MICP

Using a sodium alginate biopolymer the research in 10 proposed an environmentally-friendly alternative to improving dune sand strength. The material was studied using UCS and temperature tests.

The results highlighted that:

-

curing at temperatures between 45°C-80°C gradually decreased the UCS

-

after 7 days of curing the samples reached 90% of their *total strength

-

combining sand with sodium alginate greatly increased the CBR (California Bearing Ratio) strength compared to pure sand.

Bio-Cementation of Coral Sand using MICP with Sodium Alginate

It was found in 11 that adding a specific amount of sodium alginate in the bacterial solution could greatly improve the ability of immobilising bacteria, therefore producing an effective precipitation of calcium carbonate.

As the volume of sodium alginate increased the UCS after MICP cementation initially increased and then decreased.

Sand, PLA and PVC 3D Printing

I came across this incredible design studio called Rollo Studio who, with binder jet printing create 3D printed lighting pieces. The geometry of these pieces is very similar to how I was orginally imagining my structure, but they aren't ideal to be assembled underwater in parts.

Photo by Rollo Studio

• • •

Mentoring notes¶

From IAAC¶

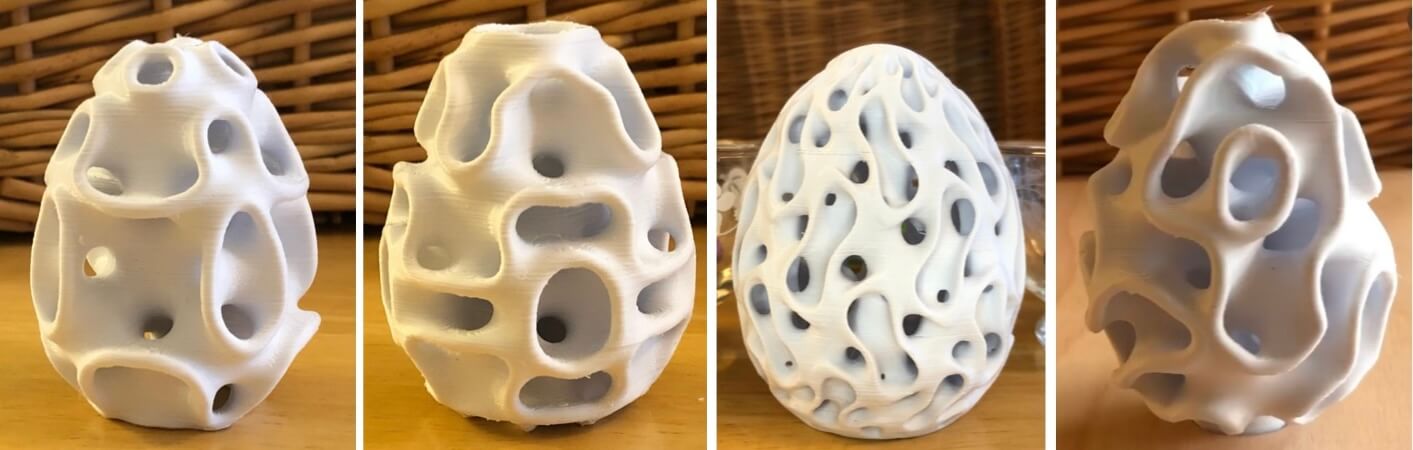

Anastasia suggested that when 3D printing the complex structures with channels, I should slice the module in half printing 2 separate pieces which fuse together during the calcifying process. Another suggestion was to print on a SLA resin printer and make a mold out of the module.

Some recommended links included:

Underwater Gardens - whom I have emailed for insights into coral reef ecology and specific conditions for artifical reefs

Soft Matters Biocalcified Textile Architecture - exposing textiles to calcifying bacteria students explored proposals of design-led applications such as bioreceptive domestic structures, urban furniture, crocheted vernacular architectures, stitched architectural ornaments and modular mashrabiya.

Article - Using Biomimicry and Bibliometric Mapping to Guide Design and Production of Artificial Coral Reefs - focuses on the designing inspired by various sustainability concepts and the contributions of biomimicry and bioinspiration. Explores a new systematic biomimicry-based design method.

Article - Coral Symbiotic Algae Calcify Ex Hospite in Partnership with Bacteria - The dinoflagellate genus Symbiodinium known for harboring important endosymbiotic algae for reef-building corals provide an important 'environmental pool' for the colonization of new coral recruits.

IAAC Blog - Framework for Coral Reef Restoration

And finally to research parametric design on gyroid structures

From RRReefs Collaboration¶

An amazing opportunity of collaboration with RRReefs has come about, with a potential of deploying my reef modules in Philippines to compare against their current 3D printed clay structures. Their reef modules are still relatively new (around 1 year old at the time of writing this - 2025) so results and findings are still ongoing.

My first call with co-founder Marie Griesmar allowed me to start understanding the processes behind reef building.

Marie mentioned some of the many factors that affect the design of a reef module.

-

the PH (at the Indonesia site the ideal PH is around 8.1)

-

the porosity

-

the shape

-

the colour (apparently pinkish/red works best, hence the choice of terracotta clay)

-

and what chemicals if any does the material release?

After much prototyping and testing, a sine wave pattern on the surface of the units proved to attract the most life and biodiversity. The surface of the brick is an essential design consideration as the way the streams and current interact with the module is very important. It is important to understand whether there are enough vertices where larvae can get stuck - hence the sine wave pattern.

The decision for RRReefs modular units was based on the fact that some locations are so remote that there is not the correct infrastructure available to transport large units to the sites. Assembling individual modules underwater allows for greater customisation and less technical transport.

I mentioned the idea of generating a gyroid structure and Marie suggested to be aware of the size of the channels as these can be quickly covered by a film of algae if they are too small. As a problem at the moment is that algae is now growing faster than larvae due to climate change, competing for space in these marine habitats.

Marine also suggested to make a mini prototype and place it in a sealed jar aquarium which is sealed. I need to further question how to efficiently make this aqaurium.

In terms of prototype testing, RRReefs in-lab tests mostly consisted of UCS and PH testing, otherwise the 3 replicas of each protoype surface were placed on a plate and were tested directly at the ocean sites, being regularly monitored every 3-6 months.

Finally Marine recommended that I have a think about how I would fix the module in the water if it broke, i.e I need to make a module that can be fixed using the original material or a biocement.

• • •

References¶

1 The Power of Gyroid Infill in 3D Printing

2 Comparing Ceramic Fischer-Koch-S and Gyroid TPMS Scaffolds for Potential in Bone Tissue Engineering

3 Bio-Cementation of Fat Clay Using MICP

4 Effect of Nanoparticle-Enhanced Bio-Cementation in Kaolinite Clay by MICP

6 3D Printing of Living Structural Composites

7 Comparison of Calcium Carbonate Production by Bacterial Isolates from Recycled Aggregates

8 Soil bacteria that Precipitate Calcium Carbonate: Mechanism and Applications of the Proces

9 Vasco Costa Delgado, C., da Cunha Santos Forman, G. A., & Antoinette Breuer, R. L. (2022). Organic Waste Bio-Based Materials for 3D Extrusion: Eggshells, Shells Sand and Coffee grains with Sodium Alginate. Convergences - Journal of Research and Arts Education, 15(29), 77–87. https://doi.org/10.53681/c1514225187514391s.29.133

10 Strengthening of Dune Sand with Sodium Alginate Biopolymer

11 Bio-Cementation of Coral Sand Using Microbial-Induced Calcite Precipitation With Sodium Alginate