Ideation¶

Personal history¶

My husband and I love food, fermentation, and country-living. After long tenures in business services, in 2014 we made a bold move: we became cheesemakers.

For Fabricademy I wanted to explore converting lactose and casein into biomaterials, drastically reducing our dairy’s whey wastewater.

Whey has severe polluting effects on the environment. And in 2022 we disposed 250.000 liter whey.

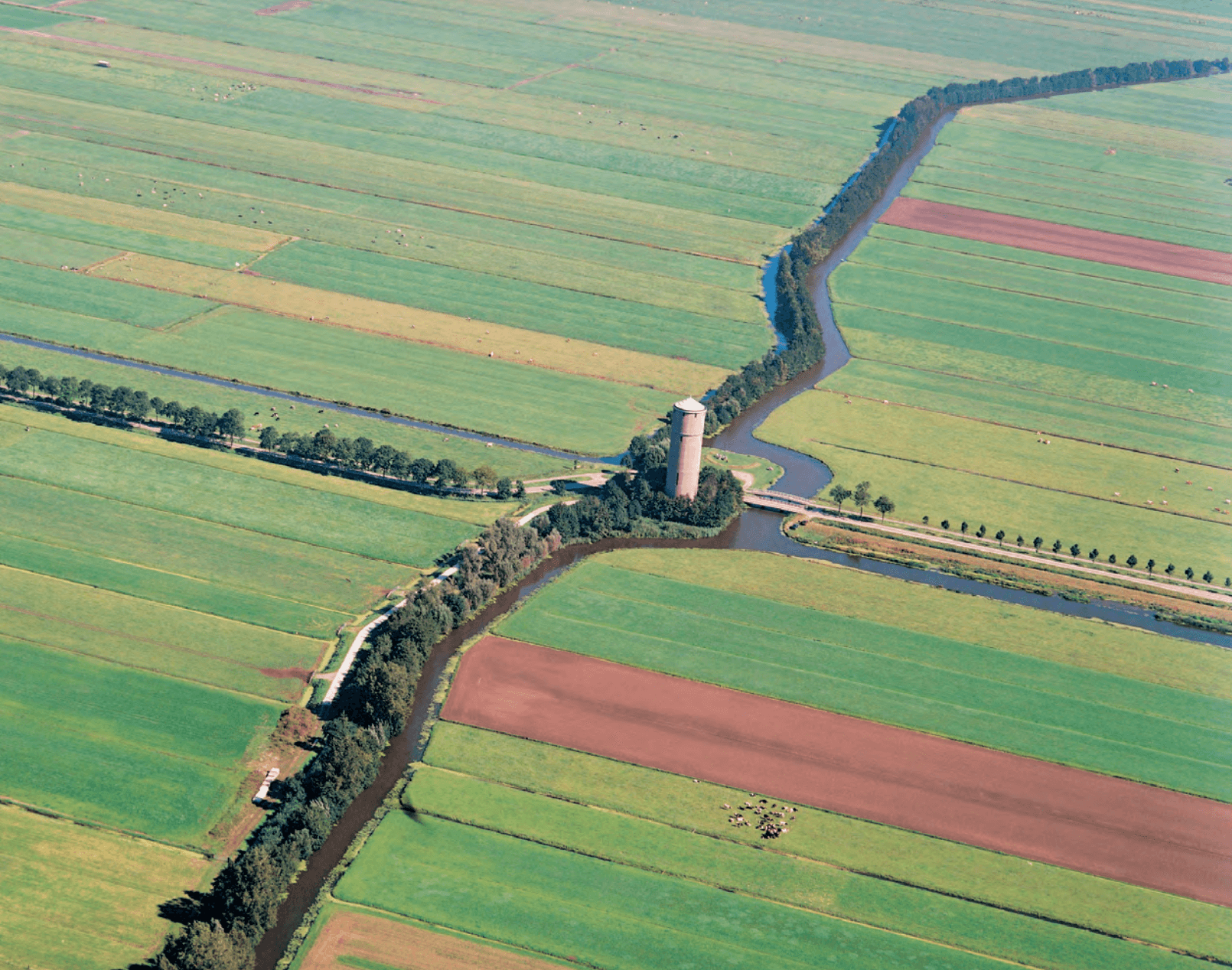

During the Fabricademy weeks, I dove in the history of my municipality Lopikerkapel and the meadow area of the Lopikerwaard. I realized that my personal history coincides with the greater story of our polder.

Polder history¶

Some highlights in the history of Lopikerwaard.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

1st century: first inhabitants¶

- River landscape

- Some dry riverbanks

- Wild peat marsh

- Hunting, fishing, foraging

11th century: great ground reclamation¶

- River landscape

- Organized landscape of arable plots and ditches

- Rise and fall of hemp and flax production

- Birth and death of fruit growing

- Growth and decline of willow toe cultivation

- Boom and bust of duck hunting

18th century: grounds are sinking¶

- River landscape

- Organized landscape of wet grassland and ditches

- Rise of dairy farming …

Now that I know this history, I feel different about our little cheese factory and the grounds it is built on. My life has become connected to this ground. I feel that my life, and my work builds upon the lives of all those people who lived here before us.

Paradigm in the nitrogen emission debate¶

But my emotion also encompasses the future. What will be the next phase for our polder?

Since a few years, dairy farming is under immense pressure in the Netherlands due to the alleged problem of nitrogen emission and how this impacts nature.

This debate is a vitriolic battle between two factions. Discussions are held in terms of declaring “good” and “bad” values. This is due to an invisible paradigm that lays beneath the discussion. Namely, the hidden perspective of framing human–nature interactions as conflict-oriented.

But suppose we would approach the debate with a new set of ideas. What if the perspective would be that harmonious coexistence between human and nature is possible?

This new paradigm might alter the debate, and free up space for constructive alternative approaches, innovations and solutions.

But is this idea of harmonious coexistence new?

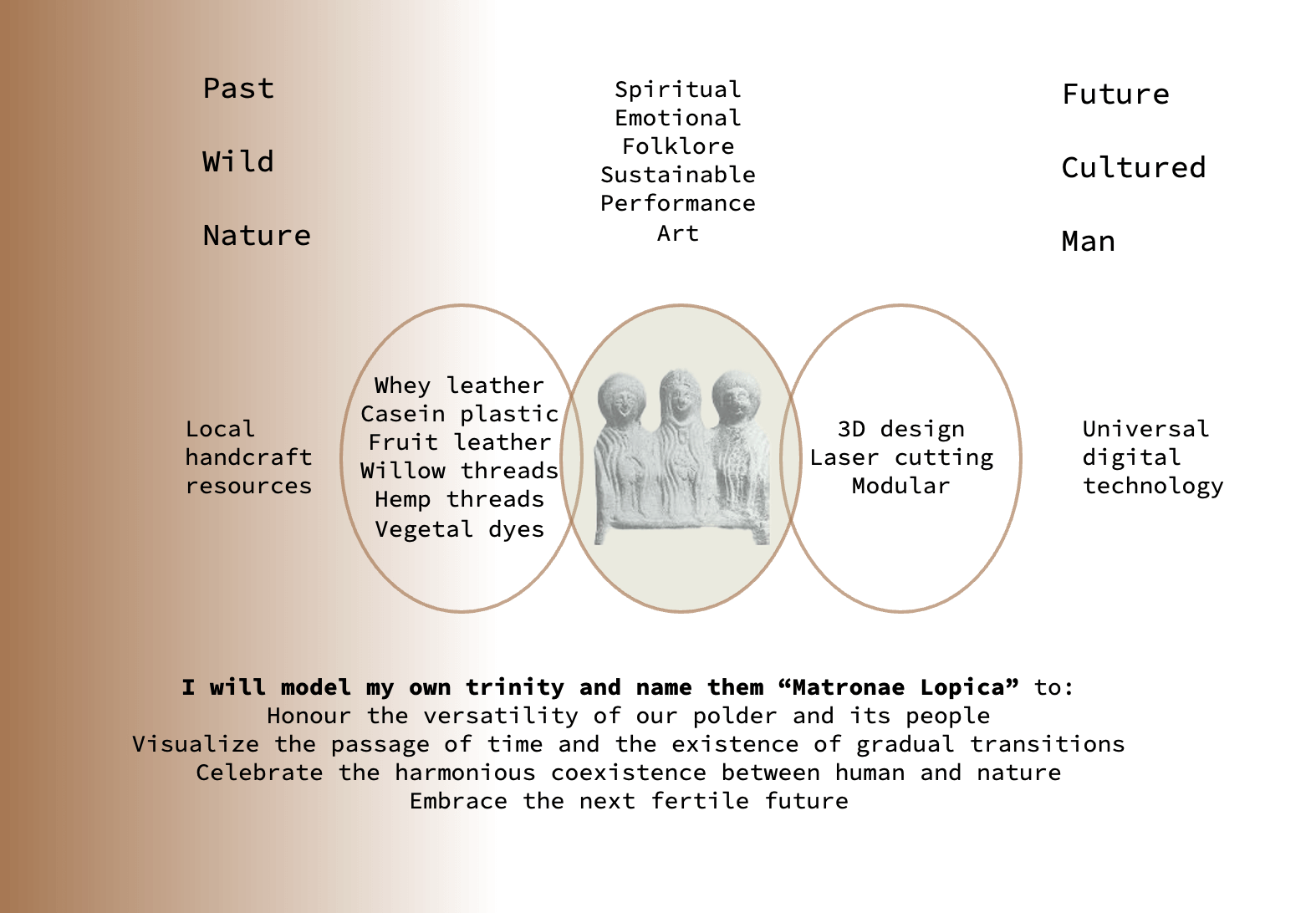

Matronae¶

Let’s go back to ancient times again to answer that question.

Before male gods came to prominence, female goddesses were primarily worshiped in Northern Europe. They often appeared in a trinity: the Matronae, or the Triple Goddess.13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23

Not far from my place in the polder, an altar of three Matronae has been found, so the Matronae-cult was present in my region as well.

As a collective, the Matronae were: - The reflection of the Mother Earth Goddess - Always connected to a specific local place - Often connected to a water source or river

In ancient times, the land was recognized as a living entity, sentient and receptive to human activity, but also quite inhuman in its nature. Prehistoric man equated the Matronae with the land itself and with the feminine fertility power active in the earth. By that power, the Matres created life, ordained fate, and sometimes brought death and destruction. In this sense, humans had to favor the Matronae.

But at the same time, it was believed that the fertility of the earth needed an input from the people. A successful harvest required the combined energy of earth, which was considered female, and humanity, which was considered male. That the Matronae appeared as a trinity was a message.

In terms of time, this concept told us that Mother Nature, including our own individual lives, always transitions gradually and cyclically through her seasons.

And the concept intended to teach us that dualistic tensions that arise in life – between light and dark, past and future, good and evil, man and nature – are always transcended by a third factor, which unites both poles.

Central project idea¶

Let’s listen to the ancient whisper of the Matronae telling us

that HARMONIOUS COEXISTENCE

between HUMAN and NATURE

through a dynamic state of GRADUAL TRANSITIONS,

is not only possible,

but a MUST for a next FERTILE FUTURE.

How¶

To honor the Matronae Lopica and reinforce the theme of coexistence, I will adhere to six principles that will guide my decisions.

1. I clean, purify, and repurpose¶

Why would we deplete virgin (natural) resources when so many (agricultural and food) waste streams, that would otherwise have few secondary uses, are fit to be upgraded into various innovative materials?

My aim is to leverage as much as possible waste streams.

Obviously, my first focus is repurposing the whey wastewater stream of our own dairy factory. In 2022 we disposed off 250.000 liter whey which contains around 2.000 kilogram of casein and 12.250 kilogram of lactose. It should be possible to valorize those organic building blocks.

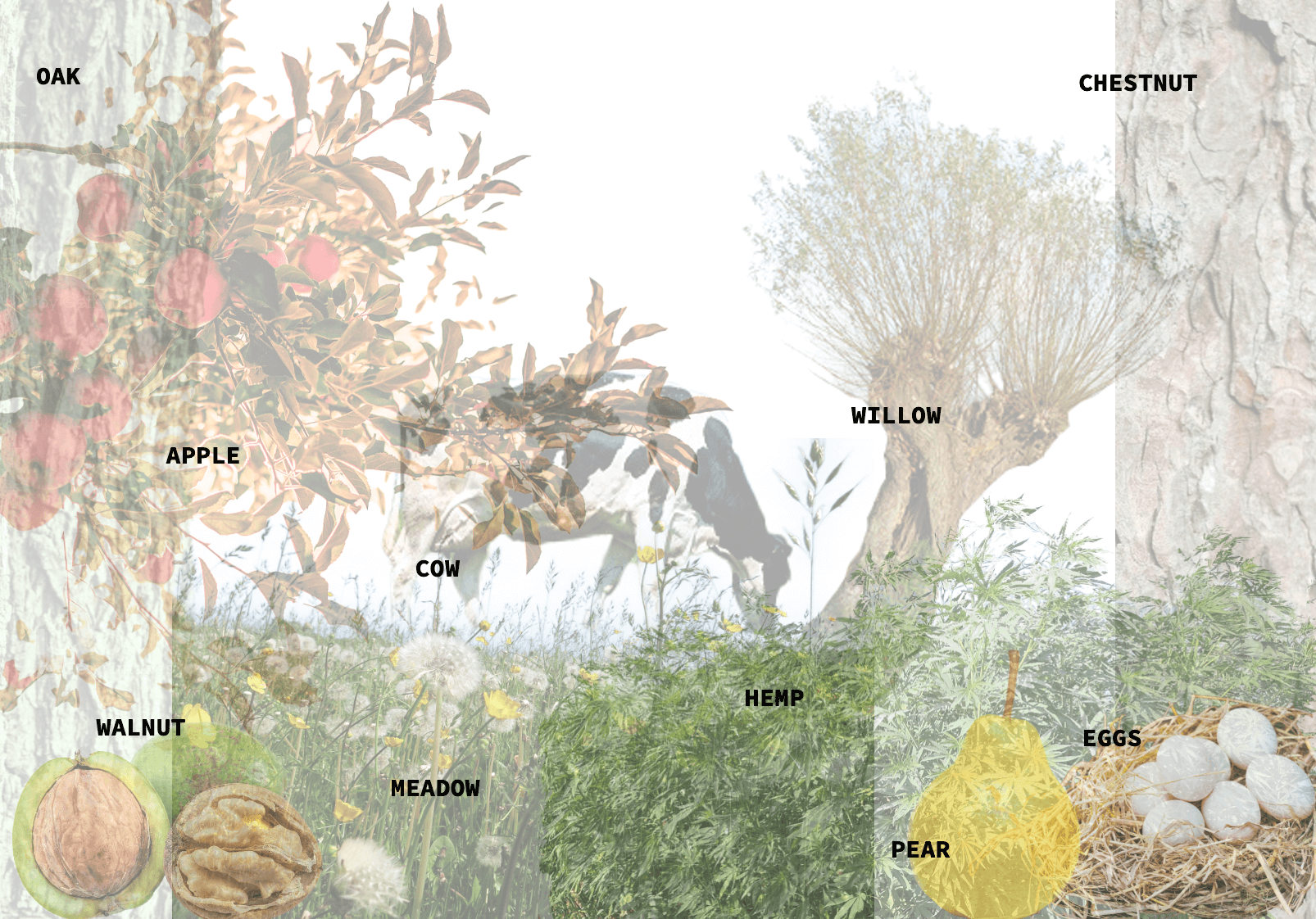

But when I look around in my polder there are more waste streams I can tap into.

Once my polder was one of the centres of fruit growing. Nowadays there are stil small orchard plots cultivated. But approximately 45% of those fruits are wasted during postharvesting, processing, distribution, and consumption.24 All these fruit seed coats, hulls, husks, peels, seeds, and pomace could be used.

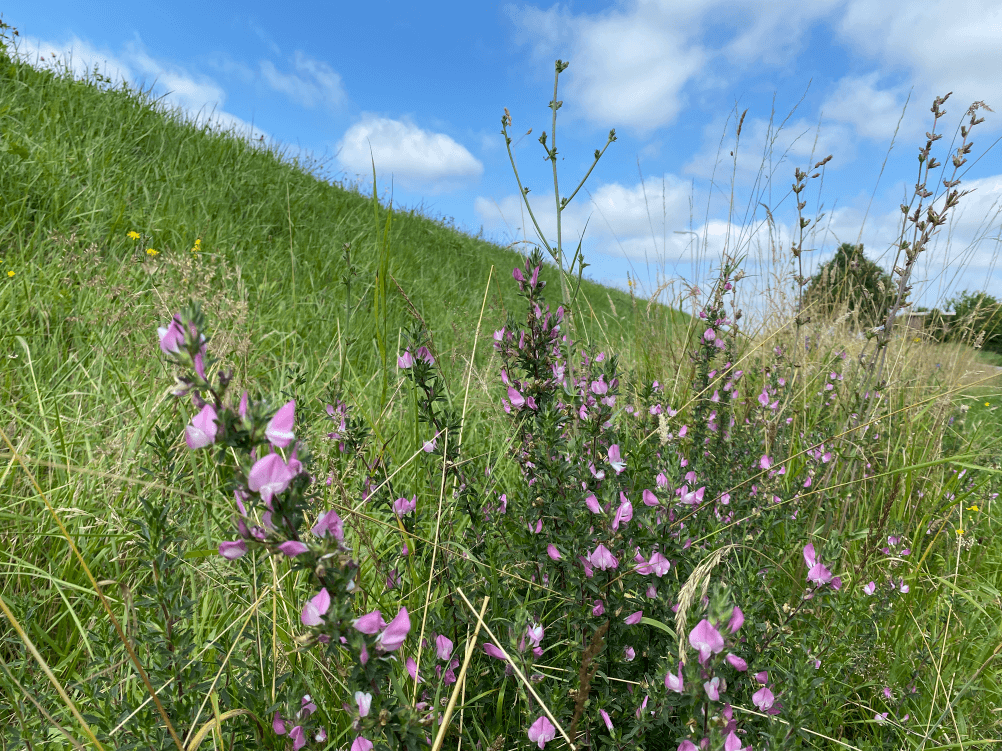

And what about the hundreds and hundreds of willows adorning the polder that are being pruned every year? What could be done with those willow toes? Or the grass from the meadows, dikes, and berms that are being mowed many times a year.

And what about the native trees, like the oak, the walnut and the sweet chestnut that have been present for ages in almost every barnyard over here? And what treasures of waste are present in the vegetable, fruit, and herb gardens that are typical for all the farms around here?

Wherever I look in my polder I see huge opportunity for leveraging waste streams and natural resources present in abundance, to make innovative biomaterials and biochromes.

2. I take and give back¶

I want the dresses for my Matronae Lopica to be fully compostable, and that is more than being biodegradable.

We often see the word ‘biodegradable’ on some products that we buy, such as soap and shampoo. But what does it actually mean? Anything biodegradable will break down quickly and safely into mostly harmless compounds. But what makes a substance biodegradable? Anything that is plant-based, animal-based or natural mineral-based product is usually biodegradable. However, they will break down at different rates depending on the original material it’s made out of and how much it has been processed. According to the American Society for Testing and Materials biodegradables are anything that undergoes degradation resulting from the action of naturally occurring microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, and algae. Although quickly is not defined, biodegradable products are broken in way less time than non-biodegradable products like plastic for instance.

Biodegradable objects can be much more than plants, as most people assume. It can be papers, boxes, bags, and other items that have all been created with the ability to slowly break down until they’re able to be consumed on a microscopic level.

Compostable means that a product is capable of breaking down into natural elements in a compost environment. Because it’s broken down into its natural elements it causes no harm to the environment. The breakdown process usually takes about 90 days. The American Society for Testing and Materials defines compostables as anything that undergoes degradation by biological processes during composting to yield CO2, water, inorganic compounds and biomass at a rate consistent with other compostable materials and leaves no visible, distinguishable or toxic residue.

Looking at the definitions of both terms it’s pretty understandable why they are so easily confused but there’s a difference. While all compostable material is biodegradable, not all biodegradable material is compostable. Although biodegradable materials return to nature and can disappear completely they sometimes leave behind metal residue, on the other hand, compostable materials create something called humus that is full of nutrients and great for plants. In summary, compostable products are biodegradable, but with an added benefit. That is, when compostables break down, they release valuable nutrients into the soil, aiding the growth of trees and plants.25

Fashion is traditionally designed without consideration of the end of a garment’s lifecycle; i.e. how to properly dispose of a garment when it is overworn or unusable in its current form. For sustainable fashion to be sustainable, fashion must be designed to consider its own disposal. The best way to do this is to design it as compostable.

Otherwise, the fashion we create or wear will eventually become waste. Of the 100 billion garments produced each year, 92 million tonnes end up in landfills or incinerators. To put things in perspective, this means that the equivalent of a rubbish truck full of clothes ends up on landfill sites every second. If the trend continues, the number of fashion waste is expected to soar up to 134 million tonnes a year by the end of the decade.26

Of course the goal is to have clothing in circulation for as long as possible. However when garments can no longer be worn, having these items turn to plant food rather than clogging landfills is the better approach.

I truly think there is beauty in using the local natural resources and waste streams from my polder to make compostable dresses, and have the dresses feed in turn the flora in the polder at the end of their lifecycle.

3. I worship local resources¶

I have never understood why consumer end-products have to be shipped around the globe. Every local community has precious resources to be self-sustaining. Granted, this will mean less choice and living more with the seasons. But is that a sacrifice or a blessing? I would say a blessing.

My dresses can be beautiful garments produced with locally available resources.

4. I search for coexistence at the material level¶

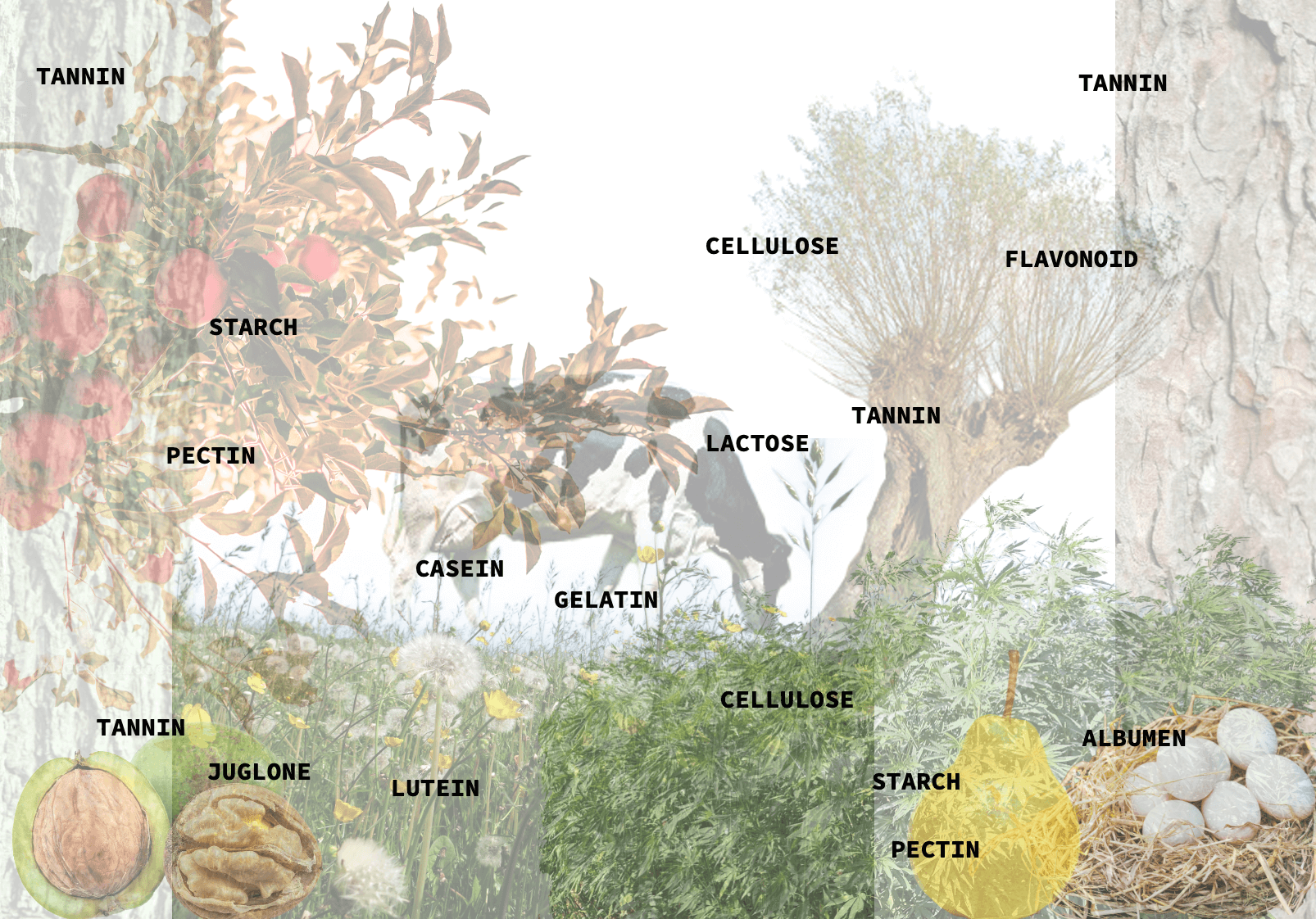

For fully compostable dresses, I need to research, develop, and produce biomaterials and biochromes. Our whey wastewater stream, containing casein, and lactose will be key in this part, alongside other local waste streams and natural resources, like fruit, hemp, willow toes, grass, trees, field flowers, weeds, shrubs, and remains from the vegetable garden, which are or have historically been present in abundance in our polder. From these building blocks I am able to make materials like alternative leathers, bioplastics, and vegetal dyes.

It would be easy to take on each of those building blocks as seperate inputs, craft seperate materials from them, and then when it comes to designing, layer those seperate outputs on top of each other in a dress, to make my point.

However, to really bring my central idea of harmonious coexistence through gradual transitions forward, I would like to take it one step further.

My main quest will be to discover if the various building blocks can be married at the material production level. What if I can combine some of those different building blocks to create new and better materials? Those type of materials would truly represent my central idea, as those materials literally merge the past and the future, the wild and the cultured, human and nature.

For this approach it is not enough to look at the history of my polder through a macro lens:

I must zoom in and study the natural resources from a micro perspective:

Would it be possible to combine casein, pectin, lutein, and cellulose to make a yellow-colored, fibre-strengtened bioplastic?

Would it be possible to combine starch, tannin, and gelatine to make a water-resistant fruitleather?

From the micro perspective, there seem to be endless possibilities to arrive at coexistence!

5. I use precious resources scarcely¶

In our dairy factory we are very aware of the precious nature of water and energy. Yes, when the tap is opened, water streams out. And by pushing a button, the cheese vat is heating up. But cheese making is a water- and energy-intensive process. And we don't take that lightly. We installed solar panels and invested in batteries to make the most out of solar power. We dug a water well. And in the near future we will invest in closing some of the process loops, to recycle and repurpose hot water, which will reduce both our water and energy usage.

I want to apply the same approach in making the materials for my dresses. Why use more water and energy than necessary?

6. I count my blessings¶

When developing innovative materials, the first focus will be to test the functional characteristics. What's their performance in elasticity, flexibility, strength, transparency, shine, water resistance, etc. But in this project, focusing on the central idea of harmonious coexistence between human and nature, I feel it is just to extend the parameters for scoring.

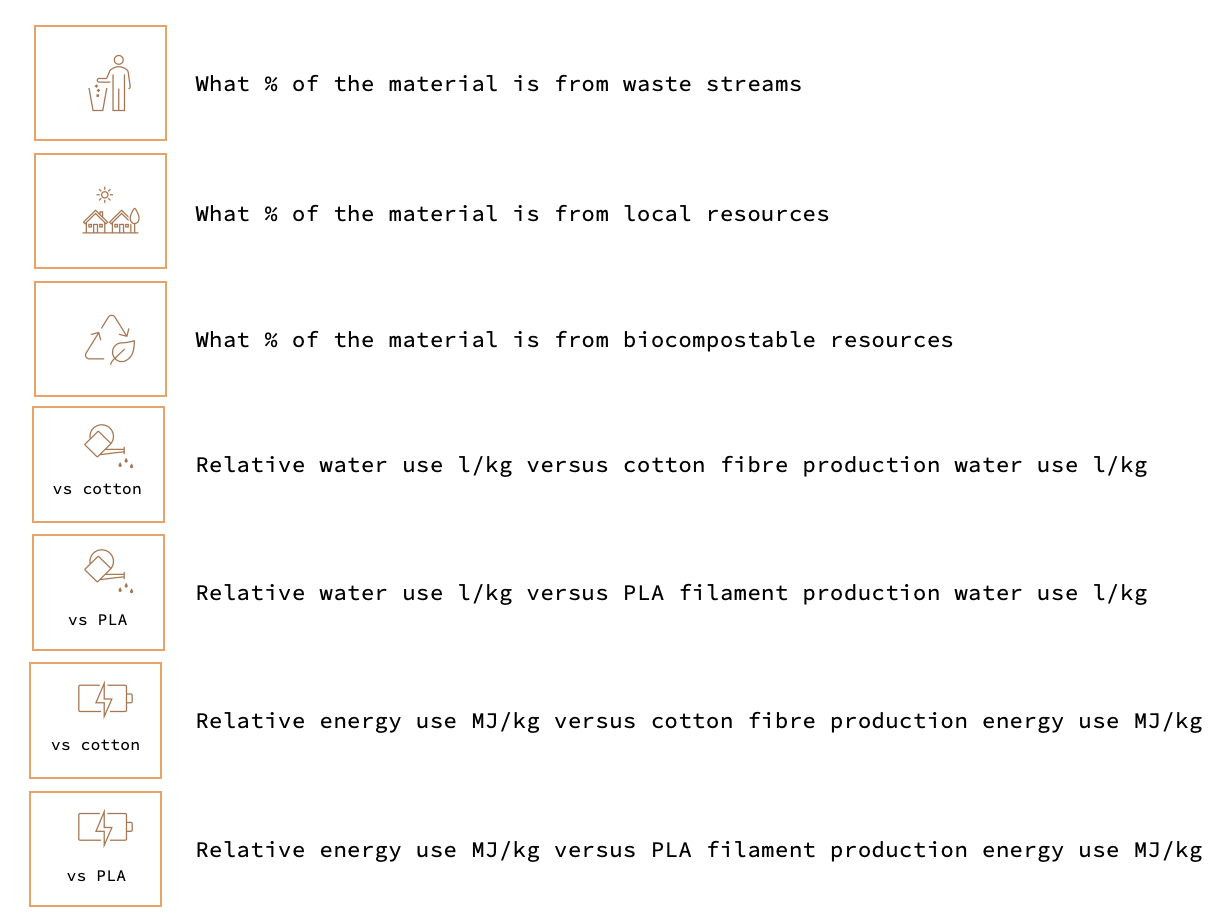

In order to adhere to my principles I will create an additional bioscoring framework for my materials.

In the bioscoring system I will measure the following:

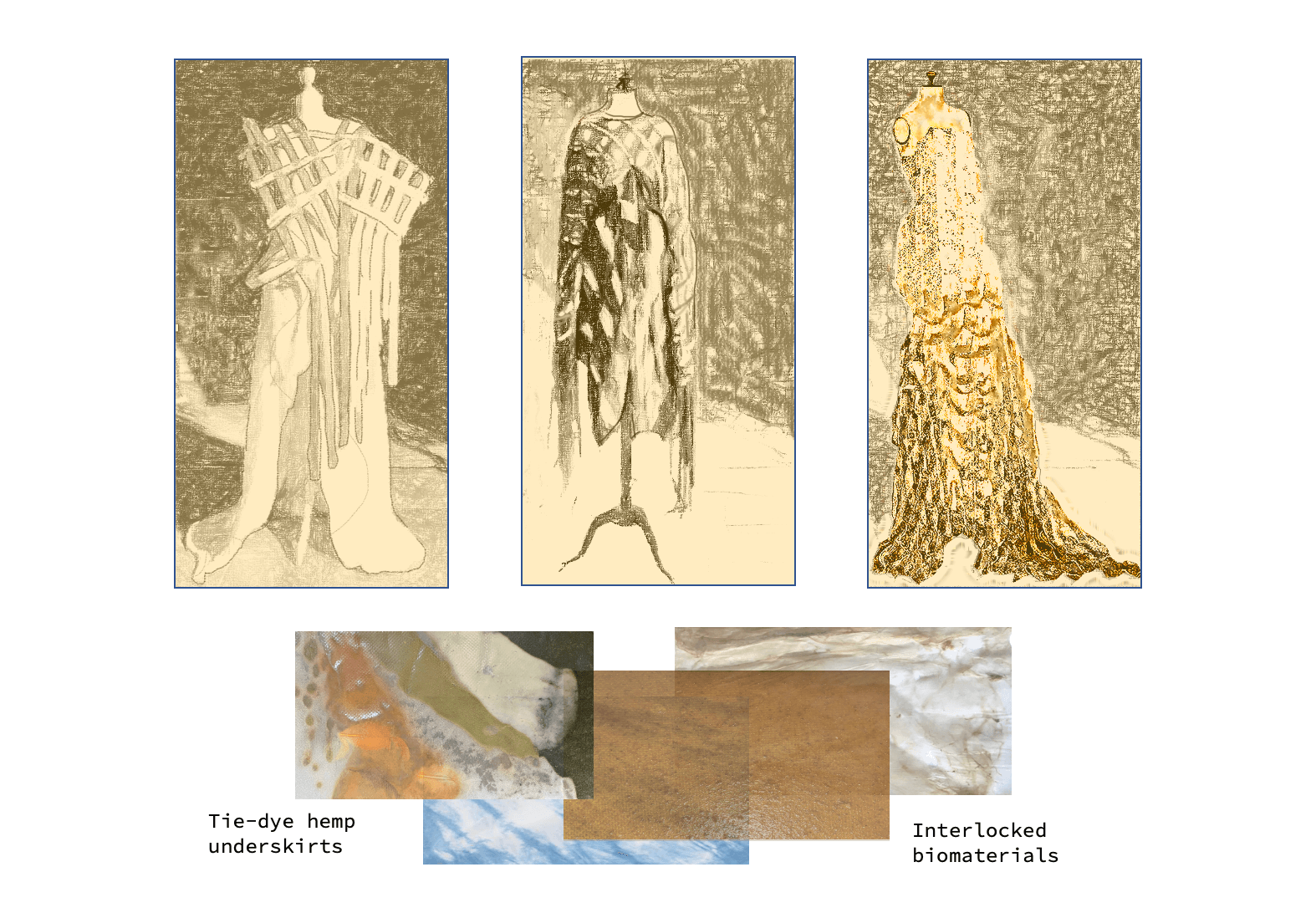

Prototype sketches¶

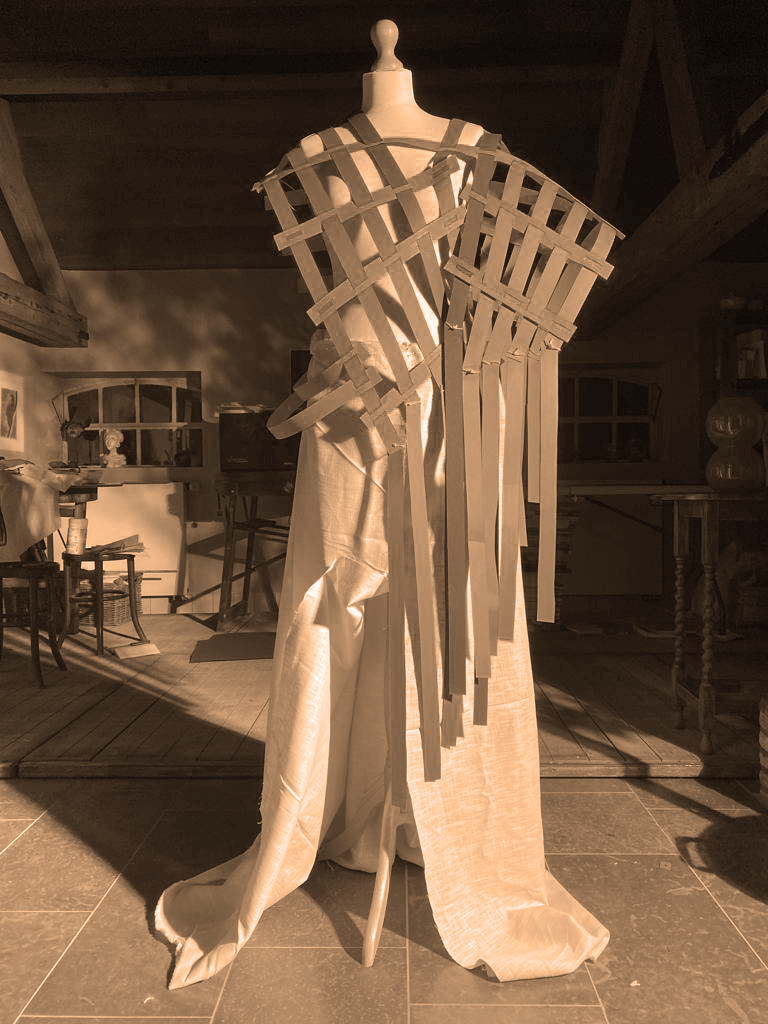

Earlier I had made some moodboards. They gave me the inspiration of potential designs for my Matronae Lopica. For all dresses I apply a layered design of stripes and combine fluid organic forms with stiff and straight lined patterns, which echoes the territory and history of the landscape. In my fabrication I must make sure each dress has a unique identity, but the three dresses together form a collective.

One of the sketches I turned into a paper prototype on a mannequin. The carton I used is a bit stiff, so the dress is not yet draping as I had envisioned. During the design phase I will need to reiterate between material characteristics and the tesselation patterns to be applied.

References and links¶

-

Regionaal Historisch Centrum Rijnstreek en Lopikerwaard archieven ↩

-

[Book - 70 Verhalen uit de archieven van Rijnstreek en Lopikerwaard] ↩

-

[Book - Canon van Nederland] ↩

-

Godinnen en vrouwelijke natuurwezens in het Keltisch oorspronggebied ↩

-

Utilization of Vegetable and Fruit By-products as Functional Ingredient and Food ↩

-

Nature's path - difference biodegradables and compostables ↩